MKM architecture + design promotes Ben McHugh, AIA, to the position of Senior Associate, growing the firm's leadership team.

How Community Platforms Can Provide Frequent Opportunities to Expand Social Capital

How Community Platforms Can Provide Frequent Opportunities to Expand Social Capital. Our instinctive desire to connect has never been clearer. We need to be around each other, connect with friends and family, and play a part in the community we call home. Unfortunately, we exist in one of the most socially connected—and most lonely—eras in human history.

While the internet has presented us with a litany of ways to communicate with one another, these interactions are often not sufficient to alleviate our sense of loneliness. According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), when Americans were asked to rank the top three areas where they felt the highest sense of community and belonging, “online communities were among the least likely to be selected (3%)” (APA, 2024). Nonetheless, we continue our growing reliance on the metaverse.

Social media’s double-edged sword makes interacting with thousands of online ‘friends’ effortless while simultaneously diverting us from in-person interactions that our well-being depends on. In this instance, and countless others, our free will often causes us to want too much of a good thing. It traps us in a cycle of unsatisfactory behavior that fails to meet this instinctive need for connection.

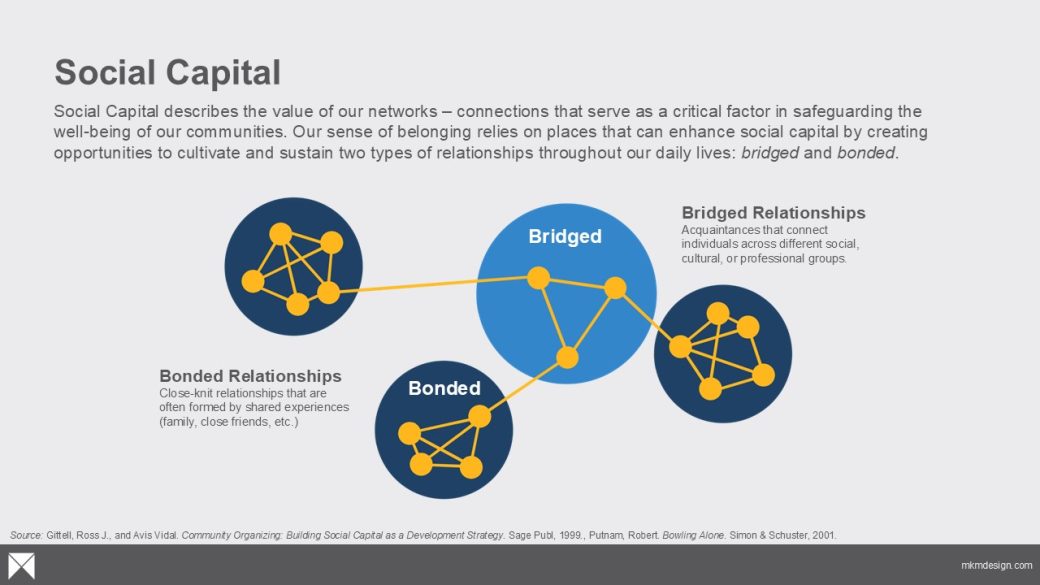

Like most issues, this, too, is multifaceted. Communities, whether virtual or physical, are intended to bring people together. The built environment contributes to bringing people together when it encourages social interaction that promotes opportunities for bridged connections to develop.

Dynamics of Social Capital

Social Capital describes the value of our personal connections. The emphasis being on value—not size.

Research consistently shows that strong social networks are among the most critical factors in safeguarding our well-being. Within these networks, various types of relationships serve different purposes. American political scientist Robert Putnam is commonly accredited with the concept of ‘Bonded and Bridged Relationships,’ which attempted to define further two key types of relationships we often rely on:

-

- Bonded Relationships are close-knit and usually formed by shared experiences with family or close friends.

- Bridged Relationships are more distant, connecting individuals across different social, cultural, or professional groups.

In his book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Putnam referred to bonded relationships as “good for getting by” and bridged relationships as “crucial for getting ahead.” Though relationships evolve throughout time, this distinction is significant, and a robust social capital requires both. [1]

Since our bonded relationships are commonly a result of the people closest to us, there is a high probability that those people have viewpoints similar to ours. When challenges arise, these people serve as our support system because they deeply know us and understand our personal experiences. That said, if our social networks consisted of only bonded relationships, we’d run the probable risk of homogenization—limiting our perspectives and siloing our opportunities.

Conversely, bridged relationships often reach across different social, cultural, and professional groups and diversify our perspectives. While these connections likely won’t be a shoulder to cry on, they expose us to new opportunities that we wouldn’t likely find in our bonded bubbles. If communities are genuinely going to bring people together, they should seek to capitalize on opportunities that encourage bridged relationships through in-person social cooperation.

Libraries are a long-standing example of social infrastructure that provides ample opportunity for cooperation. Within a library, people are exposed to other community members in a place that supports and welcomes diverse forms of cooperation. Environments like this are how communities can provide frequent opportunities to expand social capital.

In his book Palaces for the People, Eric Klinenberg notes that,

“…Places like libraries are saturated with strangers, people whose bodies are different, whose styles are different, who make different sounds, speak different languages, give off different, sometimes noxious, smells. Spending time in public social infrastructure requires learning to deal with these differences in a civil manner.” [2]

How Place Broadens Social Capital

Nowadays, many services people depend on have been automated, allowing many to go days without in-person interaction. However, understanding the consequences of isolation on well-being, our built environment should aim to nudge social interaction at every corner—literally. If bridged relationships are pathways to new growth and opportunities outside of our bonded relationships, how do the environments we live in make social interaction more viable when our incentives to do so gradually diminish? And maybe, more importantly, how can we incentivize the growth of such platforms?

Jane Jacobs, an American-Canadian activist, popularized the concept of ‘Multiplicity of Choice,’ which asserts that communities thrive when people have options. The choices available to us infiltrate our decisions and shape our everyday routines. Still, the mere existence of these choices does not adequately encourage social interaction—especially across diverse social, cultural, and professional groups. This bridge relies on the built environment.

Our communities provide a platform for us to interact with one another—when effective, they maximize the frequency of social interactions and, in turn, provide an equitable platform for cooperation. As modern communities continue to appreciate the importance of healthy placemaking, understanding the impact this will have on social capital will be increasingly important.

Frequency + Agency

While our communities cannot force us to build relationships with one another, their design can subtly spur bridged relationships by providing frequent places for cooperation. Take schools for example. They provide a collection of micro-platforms of cooperation that promote social trust, the growth of relationships, and exposure to diverse perspectives between clusters of students. But the density here matters. In schools, there is an agency to how students cooperate and interact with one another, and concurrently, there is a high frequency of exposure to new groups. Our communities can do the same, but many don’t.

Places that offer platforms for various cooperative interactions enable individuals to experience different perspectives, increasing their ability to develop meaningful relationships. The built environment’s responsibility is to expose people to frequent and diverse opportunities to expand social capital, which successively improves well-being.

By distributing cooperative platforms that nudge social interaction, we can increase our exposure to diverse perspectives and opportunities to connect. The broader and deeper our bridged relationships reach, the more potential we will have to cultivate understanding, empathy, and cooperation for one another.

Project Profile: Hartford City Public Library

Implications for Communities

Understanding social capital is not just about accumulating relationships; it also relies on the value within the diversity of one’s relationships. Our built environment can advocate for frequent opportunities to build relationships between people through diverse forms of cooperative interactions. Bridged relationships, enabled by opportunities to interact, are how our communities bring people together for a more equitable and healthy future.

We’re instinctively drawn to each other, but the success of those connections flourishes by in-person interaction, connections that rely on the built environment to provide a bridge for their sustained success.

The paradoxical hurdle we face is recalling and prioritizing our need for connection while concurrently exploring how to develop our communities effectively—by providing the social platforms necessary to cultivate and sustain the relationships that remind us we belong.

References:

[1] Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2020), 23.

[2] Klinenberg, Eric. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life (New York: Broadway Books, 2019).