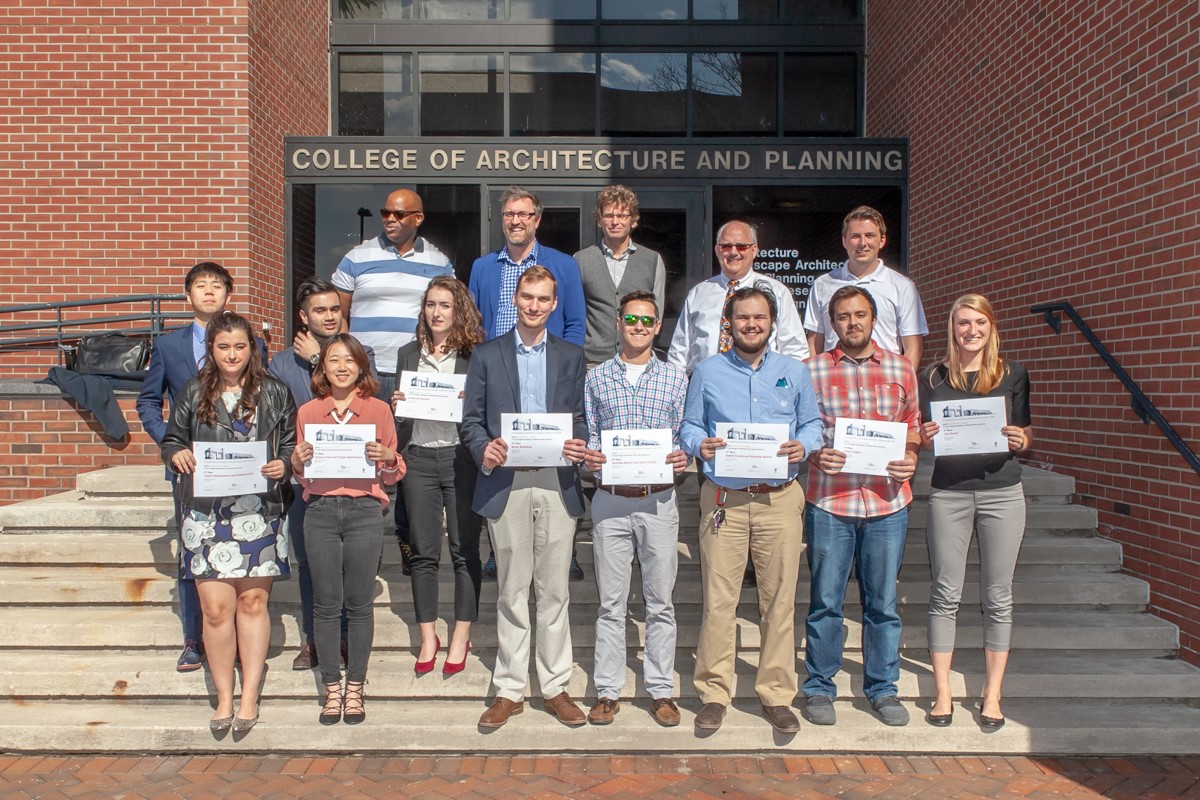

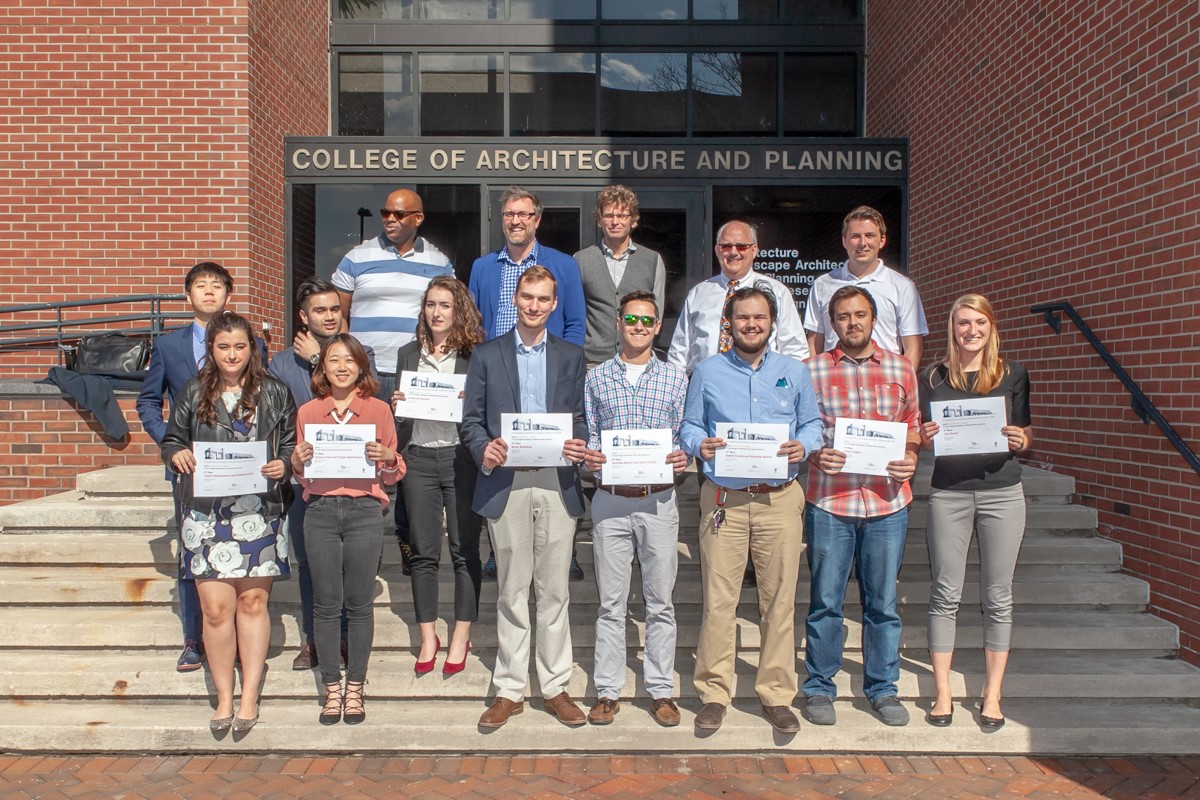

2018 MKM Third-Year Ball State College of Architecture and Planning Design Competition Award Winners

The 2018 ACSA Steel Competition for Transit Station Design was used as the basis for this spring’s six-week exploration.

Hoosiers aren’t well. Honestly, far from it. If you look at Indiana’s well-being across various indicators, our state’s poor health is undeniable. It’s a problem with no obvious solution in sight. But if we intend to provide a prosperous future for younger generations, one that aims to foster economic and cultural growth, we need to start taking our collective health more seriously.

The problem is that well-being is complicated. It is a nuanced, multi-dimensional issue that cannot simply be resolved by increasing access to healthcare. To address the unique health concerns of the 21st century, communities need integrative and innovative solutions that consider not just the physical causes and symptoms of poor health, but also the social, economic, and environmental components. To do this, we need to establish a more effective system for providing positive health outcomes – one that addresses the root causes of our well-being.

A common parable illustrates the challenges facing our declining community health: One day, three friends were walking alongside a river when they suddenly hear the cries of a drowning child. The first friend immediately jumps into the water. As he attempts to rescue the child, he notices more children nearing. Desperate to help, the second friend starts to build a raft to collect the growing number of children quickly approaching. They wade through the water, frantically grabbing branches and sticks, overwhelmed by all the children that need to be saved. In a panic they look up to the third friend for help and are upset to see him running along the shoreline. “Why are you leaving?’ they scream. “I’m not leaving,” he responds. “I’m going to go upstream to see what’s throwing these kids into the river!”

Healthcare systems where specialists are trained to respond to individuals in need provide communities with that first friend. ICU doctors, surgeons, trauma nurses and dozens of other healthcare professionals serve as vital rescuers.

Primary care physicians, supportive care teams, and numerous social service organizations constitute a community’s equivalent of the raft-building second friend. Managing our ongoing well-being and chronic diseases, they provide a safety net that protects us from growing health concerns. And just like in the story, as the need for these services continues to grow, these individuals are becoming increasingly overwhelmed.

But who is the third friend? Who is tasked with running upstream to understand and expose what is throwing us in the river in the first place? The answer to that question is less clear.

The root cause of community health is often misunderstood. Less than 20 percent of health determinants are a result of our genetic makeup or the clinical care we receive. The primary force in defining our health is found in the socio-economic factors that define our everyday routine. In fact, our zip code often plays a larger role in defining our well-being than the quality of our family physician.

Conventional healthcare services are found at the end of the river. Catching us at our most vulnerable further upstream, we see the immediate impact these our homes and neighborhoods have on our quality of life. To better understand the impact these places have on our health, communities will need to reassess how well-being is measured.

Every year Gallup-Sharecare publishes a Well-Being Index. This analysis looks at an interrelated set of five elements:

Purpose: Enjoying everyday activities and motivation to achieve goals.

Social: Having supportive and loving relationships.

Financial: Managing finances to reduce stress and increase security.

Community: Liking where you live, feeling safe, and having price in your community.

Physical: Having good health and enough energy to get things done daily.

By conducting more than 2.5 million surveys, the report is designed to illustrate how well-being varies from state to state. And the results are clear. The Midwest is unwell.

While rural states like South Dakota, Minnesota, North Dakota, Idaho, and Montana are all within the top ten healthiest states, the tristate area of Indiana, Ohio, and Kentucky have been listed in the bottom ten states since the report was first published in 2013. This is not a rural health issue; it is a Midwestern problem, one that will require a Midwestern solution.

In 2016, Indiana’s Well-Being Index score placed 46th on the list of 50 states. This score was a composite of individual rankings within the five well-being categories: Indiana ranked 47th in purpose, 49th in social, 30th in financial, 38th in community, and 44th in the physical ranking.

The Well-Being Index also looks at individual communities to compare the differences between various cities. In 2015, Fort Wayne received a Well-Being Index score of 60.3, placing the city 166th out of the 190 communities considered. While the community placed 58th for its financial ranking, it fell short in other categories. When it came to its social ranking – whether or not the citizens of Fort Wayne had “supportive relationships and love in your life” – the city placed last (190th).

Well-being is not only an indicator of community health, its directly related to community performance. “A reliable well-being metric provides community and business leaders with the data and insights they need to help make sustained transformation a reality. After all, if you can’t measure it, you can’t change it,” says Dan Buettner, founder of BlueZones. The first step to solving a problem is recognizing that there is one. Indiana is not well. And to fix it, we will need to start looking upstream.

When compared to residents of low well-being communities like Indiana, residents of high well-being communities are 12 percent more likely to learn new things (purpose); 6 percent more likely to get positive energy from family and friends (social); 16 percent less likely to worry about money (financial); 18 percent more likely to be proud of their community (community); and 25 percent less likely to have depression over their lifetime (physical). The challenge rests however, in understanding how to develop and implement economic development strategies that are specifically focused on enhancing community well-being. If we move upstream, we will likely find that the answer revolves around a more sophisticated approach to placemaking.

We need to understand what is throwing our kids in the river. To solve this problem will require an enormous effort by individuals across multiple disciplines solely focused on understanding the root causes of well-being within our communities. More importantly, it is a problem that will need “upstreamists” – people who are willing to lead us beyond an instinct to react to these outcomes and move us towards a strategy that addresses the issue at its source.

The article first appeared in the May 2018 issue of Fort Wayne Magazine.

The 2018 ACSA Steel Competition for Transit Station Design was used as the basis for this spring’s six-week exploration.

MKM is expanding the Memory Care unit, otherwise known as the Tulip Wing, at Lutheran Life Villages on Anthony Boulevard in Fort Wayne.